Transcribing Kartini: Using handwritten text recognition technology to unlock UNESCO 'Memory of the World' letters

During her internship at the Leiden University Libraries’ Centre for Digital Scholarship, Kayla Varga used an approach combining AI and human input to make reading historic letters more accessible and efficient.

Letters are among the most human of artifacts, but archaic handwriting and varying levels of preservation present significant challenges for those wishing to read and understand them. When faced with hundreds of nineteenth-century letters written in a scrawling Dutch script, the traditional path forward can be daunting: months of manual transcription, specialised palaeographic expertise, and the inevitable bottleneck of human reading speed. The Kartini collection at Leiden University Libraries' Special Collections presents exactly this challenge.

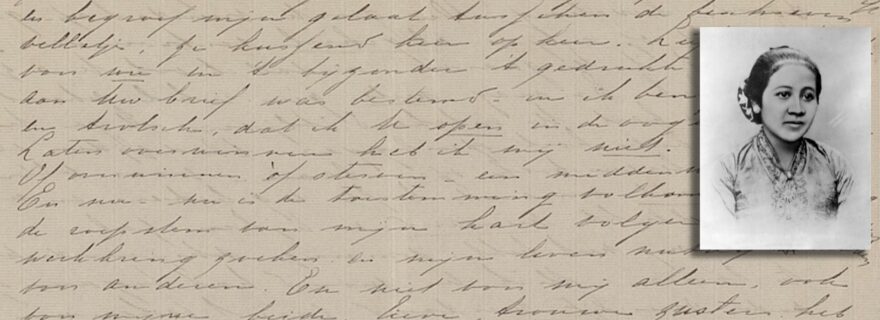

The Kartini collection consist of an archive of letters written by women’s rights advocate Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879-1904) communicating her views on Javanese culture, colonialism, religion and women's emancipation. This collection of correspondence has recently been recognised by UNESCO as documentary world heritage for its immense historical value, yet it remains largely inaccessible to readers due to the sheer amount of labour required to transcribe it.

Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) technology, specifically through the Transkribus platform, offers a possible solution. However, implementing HTR is not simply a matter of scanning documents and pressing "transcribe". It requires careful planning, iterative training, and thoughtful quality control. In a relentless battle between ink and interfaces, here is what I learnt during my internship at the Centre for Digital Scholarship, while bringing Kartini's revolutionary words into the digital age.

Written between 1899 and 1904, the vast Kartini collection presents a set of unique challenges: An archaic Dutch writing style, occasional switches to Malay, and the document quality varying from clear and crisp to damaged and indiscernible. Kartini's handwriting itself evolved over years of correspondence, with hastily written marginalia differing markedly from the carefully composed main text.

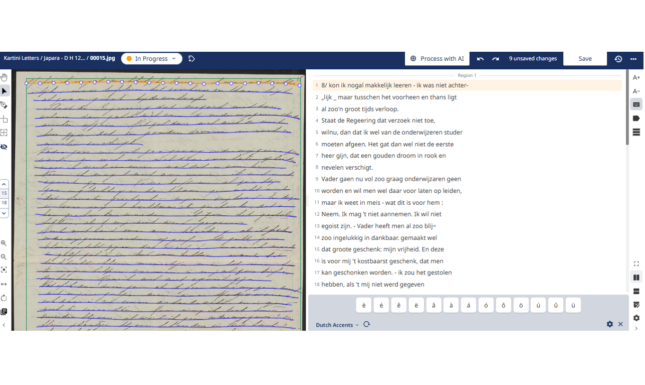

Eager to test the limitless potential of AI, I set out to train a custom HTR model using Kartini’s letters as ground truth data. This required manually transcribing pages to teach the algorithm to recognize specific handwriting styles. I began the process by meticulously transcribing 50-75 representative pages, developing consistent protocols for handling abbreviations, strike-throughs, and notations.

Once established, I trained the model through multiple iterations. Much like any stubborn bachelor student, Transkribus required patience and frequent repetition as it painstakingly learnt the differences between g’s, j’s, and z’s, often failing in its attempts to differentiate vowels. In a truly self-reflective nature, the model determines a 'Character Error Rate' or CER, indicating the quality of the model, where <10% is acceptable and below 5% is the optimal benchmark. After several refinement cycles, accuracy improved significantly. The resulting model is not perfect but functions with enough precision that human correction requires far less time than transcription from scratch.

The process progressed with Transkribus building the foundation whilst I worked to correct and construct the meaning behind Kartini’s words. The true reward of this process was that, in refining the model, I was able to dwell on Kartini’s words myself, reading her letters closely, line by line, and encountering her voice in its rawest form. Here was a young woman, not much older than I am, fighting for the democratisation of knowledge that tools like Transkribus now make possible, and for the education that I, as a woman, am now fortunate enough to enjoy.

On a practical level, the success of the model means these letters can now be transcribed and studied more efficiently, creating a foundation for both traditional scholarship and new forms of digital analysis. Yet efficiency is not the end goal; it is what allows for deeper, more human engagement with Kartini’s words.

Letters are among the most human of artifacts, imperfect and deeply personal. To entrust them solely to the non-human workings of AI would betray their essence. They deserve to be approached with the same care and intention with which they were first created. In this sense, HTR and human input together form a symbiotic answer: broadening digital access while preserving the integrity of the artifact.

This blog was edited by Tessa de Roo and Pascal Flohr

Banner image credits: Letter by Raden Ajeng Kartini to Rosa Abendanon (1900), Leiden University Libraries. Portrait of Raden Ajeng Kartini (public domain)